From Garden to Studio: a preface

A detail of our garden in the Morvan, late summer

I am proposing that this article is read as a sort of preface for future thinking articles on environmentalism, horticultural, farming and the landscape, not only through the lens of attaining self-sufficiency but also in the search of a prescient relationship between the garden and the studio, embedding a sense of creativity, art and the visual in how we live.

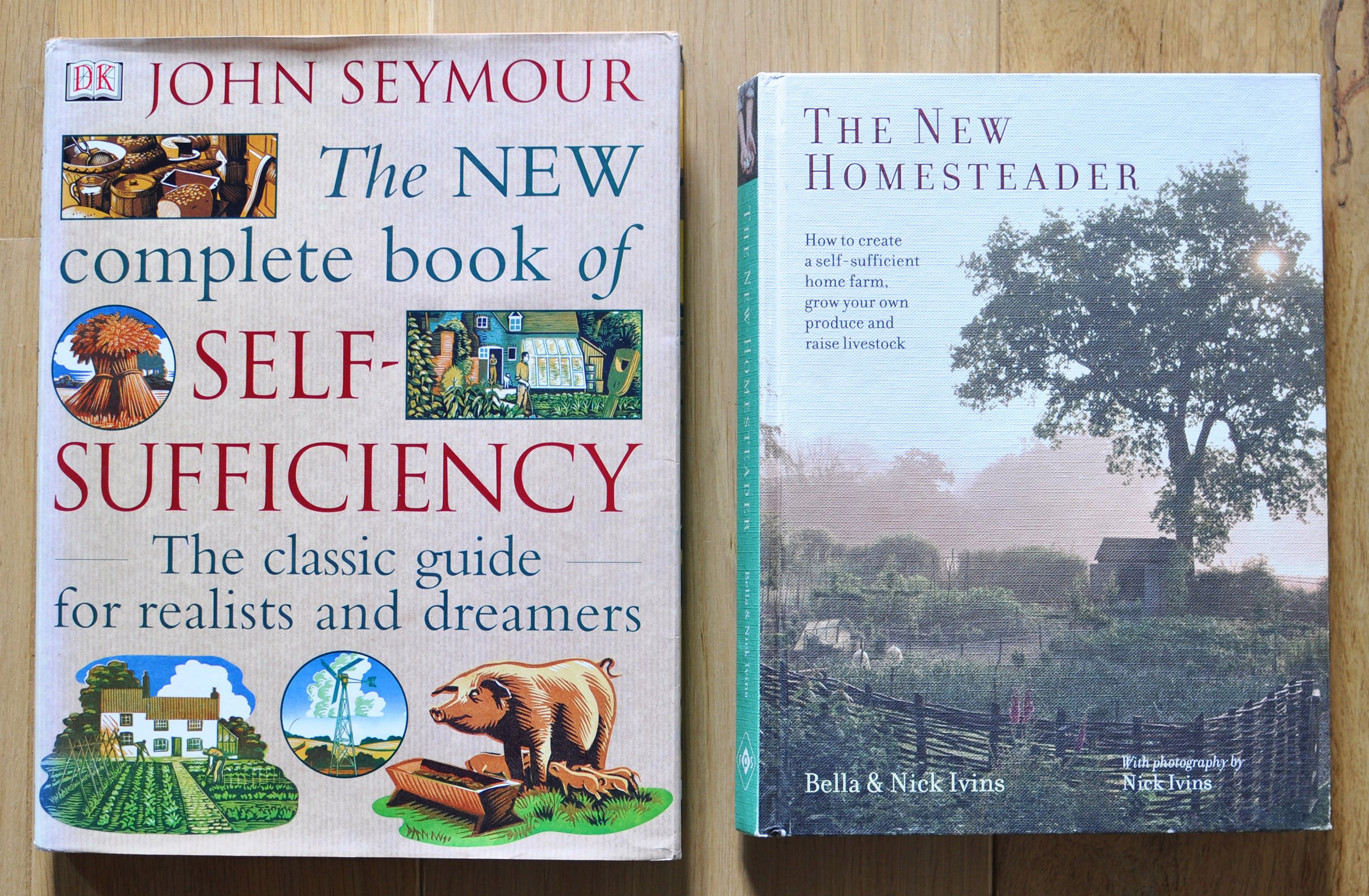

I have often taken inspiration from a good horticultural book since buying my first copy of John Seymour’s The Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency (The classic guide for realists and dreamers). Not just on ‘how to do it’ but also to nourish a sensibility, to feed the aura on what it means to work the land, where the garden becomes more than just an additional domestic space and grows into a personal and self-sustaining space; working the land for what it produces and for how it looks. I should add I am not an ‘expert’ gardener, and there are many times when I am unsure of what I am meant to be doing. However, one learns by doing, mistakes can be costly but also beneficial in knowing how to try and get it right next time. Getting it right is more than just nurturing good soil and healthy plants, it involves looking, thinking about shape, colour and texture, and often rearranging the plants into the right position. Searching for spontaneity and improvisation as much as balance and rhythm; the garden can evolve into something akin to working a painting.

Suggested reading on John Seymour’s book of self-sufficiency to propositions of the new homesteader

It is popular now not to cut the grass that often, ‘no mow May’ has become a popular shout out. However, during springtime in the Morvan the grass and weeds can be knee high in a matter of days, so some grass cutting, and hours spent weeding is advisable to prevent the overthrow of tender plants and vegetables. I still like to leave some areas to grow and be unkept when I am pushing the mower around the orchard, in its own way it becomes an exercise in drawing, creating shapes and compositions which can easily be changed and recut the following month. Though I remain ambivalent on whether a garden can be a work of art, I am conscious others might think differently and provide many examples, Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage springs to mind, or the contemporary work of Sarah Price or Piet Oudolf who both operate around the pivot of the art-garden subject.

My 1980’s copy of Seymour’s Self Sufficiency book has now been replaced by a new edition of The New Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency (2002). Seymour’s ethos, nothing should be wasted, the dustman should never have to call is a good one, and it follows on from Schumacher’s belief that there are two systems that support us, the self-reliance system and the organisation system. In the self-reliance system we are not only self-sufficient, albeit rudimentary, but we also take responsibility, conscious or unconscious, to tread lightly. In the organisation system we are subject to the vast complex of different industrial organisations where the afterlife of our waste can be falsified, obscured, unknown, and possibly becomes an infliction upon others: people and nature. And it is important to note that not everyone has the resource or inclinations to be self-sufficient in the way Seymour or Schumacher proposes. I know I am at risk of sounding sanctimonious, in truth I am as routine as the next person in producing waste in the habits of the everyday. In 2023 France introduced a new anti-waste law on packaging to try and stimulate a circular economy in how products are bought and consumed in the drive against single-use plastics.

Suggested reading on restorative agriculture and permaculture

Morvan agricultural landscape within close proximity to the residency

The thinking around treading lightly in food production and leaving areas of the garden unkept, has found some analogous approaches within the studio. Areas of the canvas being treated with some minimal sense of application, whilst other areas become quite tangled and knotted with unpredictable mark making and splashes of colour arising. I am pensive to make too much of these connections, I am confident there is no formula taking place and after all these practises are not uncommon for many artists and gardeners alike. However, where I find some commonality between the garden and the studio is in the intrinsic sense that some areas need to be changed whilst in other areas one just needs to stop and let it be, and sometimes both cases require a sense of courage and confidence in order to go with one’s instinct.

Our gardens, similar to works in the studio, are constructed, sometimes designed, and evolve as an immersive microcosm of life. The difference between the two is where the hand of nature becomes prominent in the garden, in the studio one tries to create something that can only aspire to be wild. The poet Ted Hughes made an interesting comment when talking about poetry, which I think has some analogy to how I approach painting, he said,

‘In a way, I suppose, I think of poems as a sort of animal. They have their own life, like animals, by which I mean that they seem quite separate from any person, even from their author, and nothing can be added to them or taken away without maiming and perhaps even killing them.’

So what do we make of the future? In our attempts to be more holistic between the garden and studio, we begin to realise the complexities of the endeavour, and that relatively, we are novices. Slowly picking our way through books and practises, each year we manage to grow a little more produce, learn how to preserve and store food, learn how to deal with pests and diseases in organic ways. That our thinking upon and within the garden and the studio is a network of inseparable patterns of relationships. Having been immersed in studying other artists, art history and contemporary theory for the last 30 years, I am now discovering authors new to me in the field of environmentalism and regenerative farming: Vandana Shiva, Albert Howard, Satish Kumar, Perrine and Charles Hervé-Gruyer and Mark Sheppard plus many others. As new ideas and practises emerge in the garden I suspect it may modify approaches in the studio, and I also suspect the direction of travel is not just one way, that activities in the studio, and within the residency as a whole will have an affect upon how we manage the garden, now and in the future.

Suggested reading on the brilliant permaculture research of Perrine and Charles Hervé-Gruyer

The weather changes, young trees spread and grow each season, plants sprawl, flourish and fade, insects pollinate, pests come and go, birds spread seeds. A garden like a studio is constantly in a state of becoming, where the macro and the micro invariably inform and inhabit one another, each in their own way maturing and changing over time. Along with the other environmental voices previously mentioned John Seymour’s words still resonate on how to live sustainably. I like his simple rustic honesty; he describes himself at being quite inept at times, which is something I can relate to. I will end this preface with some of John Seymour’s Foreword from the 2002 edition of The New Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency,

‘Would I advise other people to follow this lifestyle? I wouldn’t advise anybody to do anything. The purpose of this book is not to shape other people’s lives but simply to help people to do things if they decide to. … I am only one. I can only do what one can do. But what one can do, I will do!’

Suggested Reading

An Agricultural Testament, (2021) Albert Howard

Good Soil, (2017) Tina Raman, Ewa-Marie Rundquist, Justine Lagache

Miraculous Abundance, (2016) Perrine and Charles Hervé-Gruyer

Permaculture, (2017) Perrine and Charles Hervé-Gruyer

Regenerative Learning, (2022) Ed: Satish Kumar and Lorna Howarth

Restoration Agriculture, (2013) Mark Shepard

Terra Viva, (2022) Vandana Shiva

The Soil and Health, (2020) Albert Howard

The New Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency, (2002) John Seymour